2 FinTechs in Switzerland

2.1 FinTechs in Switzerland

Switzerland has a long history of private banking beginning with merchant trade passing through its land. Banking has become a symbol of Switzerland and has been a driving force in cementing its position as one of the financial centres of the world10 .

In parallel, Switzerland is also famously recognised as being the most innovative and innovation-friendly countries world-wide11. In 2015, the Confederacy officially earned this title of by ranking first in the Global Innovation Index12, and has held it ever since. According to the European Innovation Scoreboard13, Switzerland’s biggest strengths lie in attractive research systems, human resources and intellectual assets. Indeed, it is home to some of the best universities in the world including two of the top 20 best technical universities14 (ETH and EPFL). It is also the country filing the most patent requests per million inhabitants in Europe15; in 2021 Switzerland filed 969 patent applications. Holding the second position, Sweden only filed 488. The government has fostered this innovative environment over the years, creating Swiss Innovation parks16 across the country to “strengthen its position as a leader in innovation and maintain the country’s economic competitiveness”.

The place occupied by Switzerland in the FinTech scene is the fruit of strategic engineering: the government has recognised the value of the association of these two emblematic forces, and, in an effort to maintain its position in the FinTech hub ranking, Switzerland is becoming a pioneer in the FinTech world and FinTech legislation (see 3.2). This first chapter covers the Swiss FinTech scene (infra 2.1.1) and its general regulations (infra 2.1.2), and, in a case-study approach, dives into the leading A.I.-based wealthTech robo-advisory.

2.1.1 The FinTech Market

FinTechs are notoriously hard to number, due to the blurred lines there may be between FinTechs that identify as such and the emergence of traditional institutions that increasingly deliver technology-backed financial services17.

Colloquially, FinTechs may be defined as companies that apply innovative technology in the delivery of financial services18. As such, they can be classified based on these two criteria; their technology in use and service delivered19.

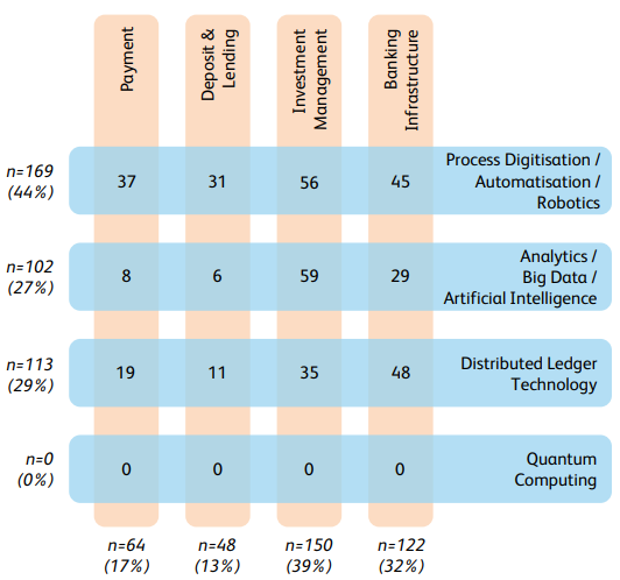

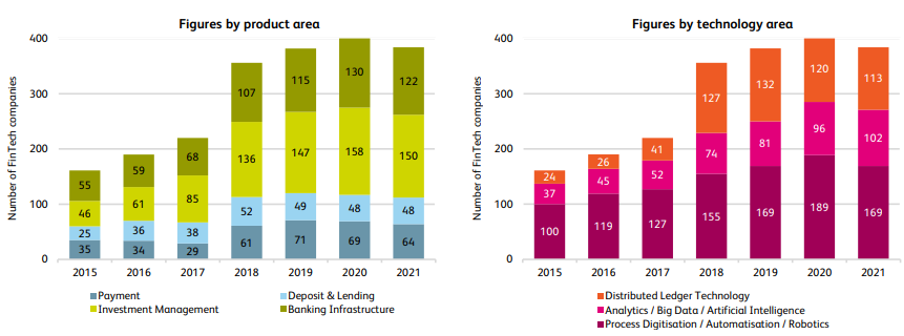

Figure 120

In 2021, 382 FinTech companies are operating in Switzerland, most of them in the investment management space (n=150) and using process digitization or automation technologies (n=169). 2021 is the first year the total company count has decreased with a negative growth of 5.2%, corresponding to a net loss of 21 businesses. However, both the median number of employees and median funding of the remaining 382 companies in operation increased21. Indeed, the number of deals rose by close to 30% of its previous four-year average making 2021 a record funding year22.

2.1.1.1 FinTech Classification

In terms of technology area, FinTechs may be broken down into process automatization/digitization, DLT, analytics/A.I. and quantum computing. To this day, no quantum computing FinTech exists in Switzerland. The most important of all three areas is therefore the automation/digitization category, followed by A.I. and Analytics. While the number of DLT and process automation firms have seen a contraction in the past year, A.I. and Analytics is the sole technology area that continues to grow in 202123.

By product area, the market may be broken down into the payment, investment management, deposit and lending, and banking infrastructure categories. None of these categories are perfectly hermetic. According to this study, investment management is the most important segment amounting to 40% of the total FinTechs24.

Figure 225

The largest crossroads between technology and product area is the combination of investment management and A.I., representing about 15% of all FinTech companies. In fact, 60% of all AI-based FinTechs operate in the investment management space, with the flagship A.I. process in WealthTech being Robo-advisory, algorithm-based asset management (3.2). When comparing the Swiss FinTech scene internationally, the Institut für Finanzdienstleistungen Zug (IFZ) study found that Swiss FinTech is on average more active in the investment management product area and in the A.I. and DLT technologies26.

2.1.2 General FinTech Regulation

In this body of work, we have chosen to restrict ourselves to the presentation of the Swiss regulations. Thus, we assume that the FinTech company is based in Switzerland and offers services to individuals or legal entities in Switzerland and therefore omit transnational aspects.

The notion of FinTech is not defined in Swiss law27. Following the IFZ subdivision in section 1.1.1, FinTechs can fall into several categories at the same time depending on the services they offer. Furthermore, FinTechs are not specifically regulated. There are no specific prohibitions or restrictions on FinTech companies or cryptocurrency-related activities28.

This, however, does not imply that FinTechs are exempt from any regulation. On the contrary; all regulations are potentially applicable. Therefore, multiple laws play a role in the development of a FinTech company. In particular, all federal laws and implementing ordinances governing financial services are potentially applicable. Indeed, pursuant to Art. 98 Par. 1 and 2 Cst., the Confederation has the capacity to legislate in the area of financial markets. In addition, circulars and other directives issued by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) as well as regulations issued by private organizations are likely to apply. Thus, data protection law, corporate law, contract law and tax law are among the legal areas that will influence the organisation of a FinTech29. It is thus necessary to examine on a case-by-case basis which laws may potentially apply to a FinTech30.

FinTech companies may hence fall within the scope of the laws mentioned below, all of which are mentioned in Art. 1 Par. 1 FINMASA, depending on their activities:

- Mortgage Bond Act of 25 June 1930 (CC 211.423.4);

- Federal Act on Contracts of Insurance of 2 April 1908 (CC 221.229.1);

- Collective Investment Schemes Act of 23 June 2006 (CISA, CC 951.31);

- Banking Act of 8 November 1934 (BA, CC 952.0);

- Financial Institutions Act of 15 June 2018 (FinIA, CC 954.1);

- Anti-Money Laundering Act of 10 October 1997 (AMLA, CC 955.0);

- Insurance Supervision Act of 17 December 2004 (ISA, CC 961.01);

- Financial Market Infrastructure Act of 19 June 2015 (FMIA, CC 958.1);

- Financial Services Act of 15 June 2018 (FinSA, CC 950.1).

According to Art. 1 Par. 1 FINMASA, the Confederation shall establish an authority to supervise in accordance with the above acts. Therefore, FinTechs may be subject to regulation and supervision by FINMA or self-regulatory organisations due to the nature and scope of their business activities31. FinTechs must ensure that they comply with the financial regulations applicable to their business model prior to any activity and ensure that they obtain any necessary authorizations or face administrative or criminal sanctions32.

According to the Federal Court, the main objectives of the financial market legislation are the protection of investors and the fairness of the capital market33. The laws mentioned above address these general objectives. Thus, these regulations aim to protect both the function of the financial market (Funktionsschutz) and the participants in that market (Kundenschutz)34. The two goals are closely linked and they are also relevant for FinTech35.

The purpose of the protection of the function of financial markets (Funktionsschutz) is to ensure that the financial market, as an institution, remains operational and to prevent it from failing. In this way, the confidence of market participants is guaranteed, allowing them to continue investing and trading. The protection of the function of financial markets aims also to minimize systemic risks. That is to say, to reduce the risks due to the interconnections between the different actors of the financial market since the bankruptcy of one can have a negative impact on the others36.

The protection of market participants covers investors, creditors and insureds. This protection is initially based on the idea that financial market participants are in a weaker economic position and are less well informed than institutions and therefore require greater protection 37.

Further, the rules of Swiss financial market law are adopted following several general principles of legislative technique:

First, financial regulation is based on principles or rules. This means that the objective and principles of regulation are defined by the legislator, but not the manner of achieving the goal. Such an approach strikes a balance between the economic freedom of business and legal certainty. The Swiss legislator sometimes moves away from purely principle-based regulation to a mixed approach between principles and rules 38.

Secondly, Swiss regulation is also based on the risks presented by the activities of financial entities and products since the legislator is not in a position to regulate and monitor all activities. Such regulation has a preventive effect. It consists, in the first instance, of identifying the risks that need to be regulated. In a second step, it is a matter of determining what level of risk can be reasonably taken by an entity. Once the threshold is exceeded, measures to prevent the risk from happening must be taken 39.

Third, the regulation seeks to be as technologically neutral as possible (technology-neutral)40. This means that regulation should not differ depending on the technology used to carry out an activity41. This implies that activities with the same level of risk should be regulated in the same way regardless of the technology used. This is an essential principle that allows the principles of proportionality (Art. 5 Cst.) and economic freedom (Art. 27 and 94 Cst.) of financial market participants to be respected42. It also creates a level playing field between innovators and traditional providers who engage in comparable activities and presents similar risks43

Finally, financial regulation can be based on an activity-based approach or an entity-based approach. In Switzerland, the legislator has traditionally regulated certain sectors of the financial market. However, the legislator has recently favored regulating the financial system in a cross-sectoral manner44. This is what the legislator has done by adopting the FinIA and the FinSA, two laws that are of particular interest to us in this work.

FINMA is open to an innovation-friendly and technology-neutral approach. Similarly, Swiss policymakers have affirmed a liberal strategy regarding the regulation of new technologies in the FinTech sector45.

On 1 January 2020, two financial market laws, the FinSA and the FinIA, entered into force. They will be detailed through the lens of robo-advisory in section 3.1. In addition, on September 25, 2020, the Parliament approved the new Federal Act on the Adaptation of Federal Law to Developments in Distributed Electronic Register Technology (DLT Act), detailed in 4.2. Finally, from September 2023, the new revised federal law on data protection (DPA) will come into force, also examined in 3.1.3.

2.1.2.1 FinTech-specific Incentives

The government keeps the digitalisation central to its economic competitiveness strategy46. As such, it has developed favourable conditions for the FinTech industry beyond its federal positive legislation to ease regulatory hurdles based on three pillars47. These reforms were initiated by the Federal council in 2016 through the Bank Ordinance, with the two first pillars coming into effect on August 1st 2017, and the last on January 1st 2019.

First Pillar: Funding

Funding is abundant in Switzerland, from seeds to traditional financial institutions eager to buy an equity stake in later stage companies48. In particular, Crowdfunding has shown rapid growth recently: the first crowdfunding platform in Switzerland was founded in 2008 and the number increased from 4 platforms in 2014 to over 38 today49. CHF 2.23 billion has been raised through crowdfunding since 200850. In per capita crowdfunding volumes, Switzerland is operating at ⅔ of the volume of the USA51.

Relai, whose founder and CEO Julian Liniger we interviewed for this paper, is currently using the crowdfunding platform Crowdcube for a crowdfunding round. With 25 days to go, they’re already gathered 126% of their target, raising EUR 1,901,210 from 409 unique investors.

This increase in crowdfunding was engineered by the legislator, facilitating conditions through the introduction of the FinTech regulation on August 1st 2017. This was done through the following amendment in the Bank Act that extended the holding period through crowdfunding that does not count towards a banking license from 7 to 60 days52.

Second Pillar: Regulatory Sandboxes

According to the United Nations Secretary General’s Special Advocate for Inclusive Finance and Development, regulatory sandboxes are “a regulatory approach […] that allows live, time-bound testing of innovations under a regulator’s oversight. Novel financial products, technologies, and business models can be tested under a set of rules, supervision requirements, and appropriate safeguards53. This usually refers to not applying all or part of the current regulations so that business operators can test and verify new products and services using new technologies by first launching them on the market under certain conditions (period, location, scale restrictions, etc.). It is a system that rationally improves regulations based on data collected in the process. It enables to promote new technologies through limited demonstrations in the market while verifying safety issues caused by the technology in advance54.

Empirical evidence from Cornelli et al. (2020) shows that sandboxes facilitate access to capital by reducing asymmetric information and regulatory costs. Although the exact mechanism that helps firms in a sandbox has not yet been identified, the positive effect of sandbox entry on capital raised is particularly pronounced for smaller and younger firms, considered more opaque and hence subject to more severe informational friction55.

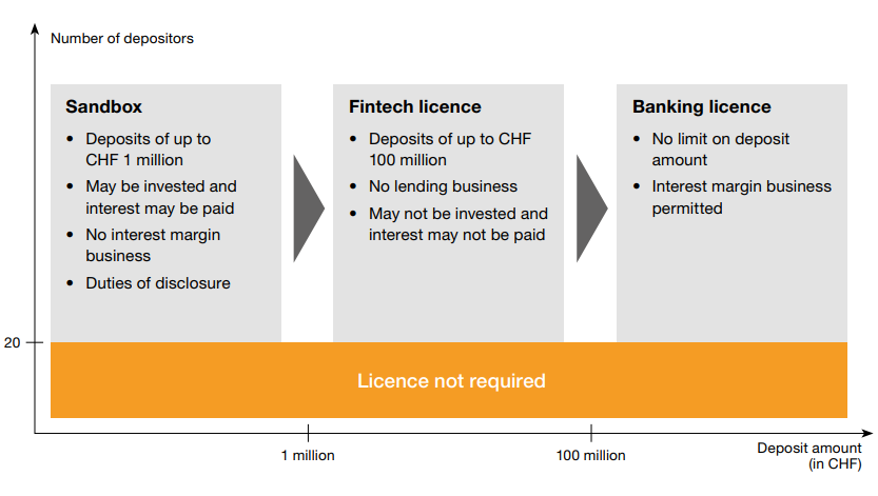

The regulatory sandbox introduced in 2017 allows deposits from the public without triggering a banking licence requirements as long as (Art. 6 Par. 2 BankV):

the deposits accepted do not exceed CHF 1 million;

no interest margin business is conducted; and

depositors are informed, before making the deposit, that the person accepting the deposits is not supervised by FINMA and that the deposits are not covered by the Swiss depositor protection scheme56.

Third Pillar: FinTech Licence57

Under a new banking licence category also called “Banking License Light”, FINMA may authorise companies that are not traditional banking companies to “accept deposits from the public up to a maximum threshold of CHF 100 million as long as deposits are not invested and no interest is paid on them”58. This new category alleviates a number of requirements around minimum capital, capital adequacy and liquidity, governance, and risk management with the aim of promoting innovation.

Figure 359

Tax Competition

While there are no specific taxation incentives uniquely targeted to the FinTech industry, the ordinary tax rate in Switzerland can be as low as 12%. This is a competitive, “business-friendly” rate (2.1): on average, OECD countries levy 21.7% corporate tax rate and the world average sits at 23.54%60.

Further, start-ups who decide to locate their tax domicile in “structurally less developed regions”61 of Switzerland may benefit from a tax holiday on both the cantonal and federal level. There are also participation deductions for realised profit benefits under certain conditions. Swiss residents also do not have capital gains tax levied on private assets. Annual wealth taxes can be lessened for start-up investors if the companies are valued at their substance value, as may be done in the canton of Zurich62.

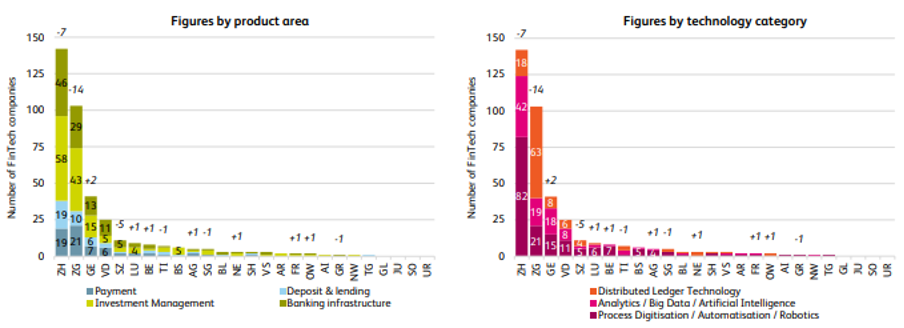

Zug, the second most popular canton to set up operation for FinTechs levies en 11.9% rate on corporate taxes and a 0.07% tax rate on capital gains63.

Figure 464

References

“The Global Financial Centres Index 31”, accessed 29 April 2022, https://www.longfinance.net/programmes/financial-centre-futures/global-financial-centres-index/gfci-publications/global-financial-centres-index-31/.↩︎

“Global Innovation Index 2021: Innovation Investments Resilient Despite COVID-19 Pandemic; Switzerland, Sweden, U.S., U.K. and the Republic of Korea Lead Ranking; China Edges Closer to Top 10”, accessed 29 April 2022, https://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/articles/2021/article_0008.html#:~:text=Switzerland%20 remains%20the%20world%20 leader,in%20the%20past%20three%20years.↩︎

“Global Innovation Index 2021: Innovation Investments Resilient Despite COVID-19 Pandemic; Switzerland, Sweden, U.S., U.K. and the Republic of Korea Lead Ranking; China Edges Closer to Top 10”, accessed 29 April 2022, https://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/articles/2021/article_0008.html#:~:text=Switzerland%20 remains%20the%20world%20 leader,in%20the%20past%20three%20years.↩︎

“European Innovation Scoreboard: Innovation performance keeps improving in EU Member States and regions”, accessed 29 April, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_3048.↩︎

“World University Rankings 2022 by subject: engineering”, accessed 7 May 2022, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2022/subject-ranking/engineering#!/page/0/length/25/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats.↩︎

“European Patent Filing Reached Record Number in 2021; Huawei Largest Applicant”, accessed 4 May 2022, https://www.ipwatchdog.com/2022/04/05/european-patent-filings-reached-record-number-2021-huawei-largest-applicant/id=148182/#:~:text=Ranked%20by%20the%20number%20of,fell%20by%2018.6%25%20to%20108%2C799. ↩︎

“Swiss Innovation Park”, accessed 7 May 2022, https://www.sbfi.admin.ch/sbfi/en/home/research-and-innovation/research-and-innovation-in-switzerland/swiss-innovation-park.html.↩︎

From one study/report to another, numbers may differ based on the working definition in use. Consideration of particular importance for Chapter 2.↩︎

Favrod-Coune and Pignon (2021) , pp. 94-95.; Flühmann and Hsu (2021) , p. 287.↩︎

BGE 139 II 279, rec. 4.2; BGE 144 IV 52, rec. 7.5.↩︎

Eckert (2019) , N 448-450.; Favrod-Coune and Pignon (2021) , p. 99.↩︎

Flühmann and Hsu (2021) , p. 287.; Favrod-Coune and Pignon (2021) , p. 94.↩︎

“Digitalisation of the financial sector”, accessed 3 May 2022, https://www.sif.admin.ch/sif/en/home/finanzmarktpolitik/digitalisation-financial-sector.html.↩︎

“Briefing on Regulatory Sandboxes”, accessed 6 May 2022, https://www.unsgsa.org/sites/default/files/resources-files/2020-09/FinTech_Briefing_Paper_Regulatory_Sandboxes.pdf.↩︎

“Regulatory Sandbox”, accessed 6 May 2022, https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/regulatory-sandbox.↩︎

“Digging for gold: How regulatory sandboxes help FinTechs raise funding”, accessed 3 May 2022, https://voxeu.org/article/how-regulatory-sandboxes-help-FinTechs-raise-funding.↩︎

“FinTech licence“, accessed 3 May 2022, https://www.finma.ch/en/authorisation/FinTech/FinTech-bewilligung/.↩︎

“FinTech licence“, accessed 3 May 2022, https://www.finma.ch/en/authorisation/FinTech/FinTech-bewilligung/.↩︎

Source: “The Swiss FinTech license”, accessed 4 May 2022, https://www.pwc.ch/en/publications/2020/The%20swiss%20FinTech%20license_EN_web.pdf.↩︎

“Corporate Income Tax Rates in Europe”, accessed 3 May 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-tax-rates-europe-2022/#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20European%20OECD%20countries,was%2023.54%20percent%20in%202021.↩︎

“Corporate Tax Rates and Tax Rates for Individuals for 2020 in the Cantons Zug, Lucerne, Zurich, and Schwyz”, accessed 3 May 2022, https://www.reichlinhess.ch/en/2020/02/14/corporate-tax-rates-and-tax-rates-for-individuals-for-2020-in-the-cantons-zug-lucerne-zurich-and-schwyz/.↩︎